Beluga Whales

Calling and Hearing: "Sea Canaries"

Belugas are known as a highly social and vocal species. While they are capable of many different sounds such as whistles, pulsed sounds, clicks, and combined sounds, belugas seem to use and attribute certain sounds in certain contexts. Additionally, belugas seem to dedicate whistles, pulsed and noisy calls, and combinations of the two for communication. Meanwhile, clicks are almost entirely used for echolocation.

Vocalization/Calling

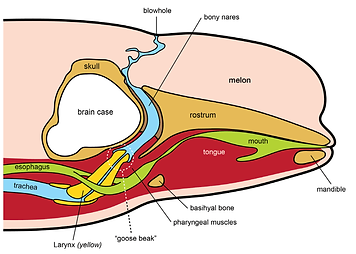

Belugas, like other delphinid odontocetes, contain a vocal fold structure within the larynx that may be used to produce certain sounds. However, a majority of the sounds (whistles and clicks) that belugas produce seem to utilize the nasal region in the head (Frankel, 2008). Additionally, belugas have a pair of "monkey lips", or dorsal bursae structures known as the MLDB complexes, which are located in the top part of the head and just below the blowhole. As belugas are able to make combined calls, these whales seem to have independent control over each complex. The MLDB complex contains two lipid-filled sacs that connect to the "monkey lips", which jut into the nasal passage (Frankel, 2008). When a beluga creates a vibration with the MLDB, the vibration is transmitted via the melon, an area in the head concentrated with lipids. Uniquely, belugas are the only species of the Odonteceti capable of controlling and changing the shape of the melon (Fig. 1; McLendon, 2021). This may allow the beluga to adapt to variation in sound transmission, resulting from movements in pelagic environments and in less saline estuarine waters (Frankel, 2008).

Figure 1: Above is a diagram of the beluga's upper body. The "goose beaks" are also known as "monkey lips" which compose the MLDB complex.

Beluga calls are categorized according to frequency contour or shape, range, harmonic intervals, and combinations of sounds. The difficulty of measuring these calls owe mainly to gradation, which is the slight variations between call types that make them difficult to categorize. Despite this complexity, there seems to be three general call categories: whistles, pulsed and noisy calls, and combined calls. Whistles typically are narrowband tonal sounds that can change in the fundamental frequency over time and are used over short distances. Pulsed calls are several short pulses that are separated by harmonic intervals, while noise calls are calls that lack distinct pulses. Pulsed and noise calls do not have specified contours and are usually used across large distances, with pulsed calls demonstrating a wider range than whistle calls. Combined calls can come in two forms, consisting of a call with a whistle and a noisy or pulsed portion or a call composed of two overlapped calls (Chmelnitsky & Ferguson, 2012; Garland et al., 2015).

While the proportion of whistle to pulsed and noisy calls to combined calls varies across different populations and regions, the overwhelming pattern across belugas is a heavy reliance on whistle calls. In a Canadian beluga population, Chmelnisky and Ferguson (2012) found that whistles accounted for almost two-thirds of all measured whale calls. The whistles also had six to seven contour types with three to five subtypes categorized under each of the contour types, totaling 22 different whistle calls. The most common whistles seem to be ascending whistles, flat whistles, and descending whistles (Chmelnitsky & Ferguson, 2012; Garland et al., 2015). Pulsed and noisy calls (around 15 call types make up around a quarter of all calls, while combined calls (around six or seven call types) accounted for the remaining ten percent (Chmelnitsky & Ferguson, 2012). Overall, whale calls could range from 200 Hz to 20 kHz in frequency (Garland et al., 2015). The different meanings and purposes behind many of these varying calls have yet to be determined, as more data may be needed.

As for the differing percentages that the belugas used, factors such as variation in acoustic environment, beluga behavior state, spatial distribution amongst belugas, and more may be responsible. As mentioned earlier, pulsed and noisy calls have a larger frequency range that may make them more useful in situations where belugas have to communicate over long distances, while high-frequency whistles can be used for short distances (Garland et al., 2015). Whistles might be used between members of a pod as a means of keeping close together, as well as identifying members individually and by group. When there is environmental noise or nearby prey, belugas can alter the call frequency and duration. There is possibility that noisy calls are used as contact certain belugas regarding certain information about a group or an individual. The function(s) of combined calls are the least understood, but Garland et al. (2015) suggests that the calls' high directionality may display information on the caller's direction of movement and its orientation to the listener. This information could then be used to synchronize movements or continue communication.

Hearing

Belugas have extremely sensitive hearing and are able to detect sounds as low as 4 to 100 kHz (less than 80 dB) to sounds higher than 150 kHz (Mooney et al., 2018; Castellote et al., 2014). This hearing is used for foraging, navigating, and communicating with others, which arguably makes audition its most important sense. Belugas show similar abilities in the wild and in zoological settings, which makes studying beluga hearing in both environments very useful. The inferior colliculus in whale brains is key to the listening process for echolocation and for hearing mating, identification, and other whale calls.

Anthropogenic noise is a big problem, as this interferes with the belugas' ability to communicate effectively and can lead to high frequency hearing loss due to the belugas' hearing sensitivity. Among the most dangerous man-made underwater noises are geophysical seismic activity, construction sounds, and explosive sounds from military bases (Castellote et al., 2014; Beluga Whales, n.d.). Many belugas who could not hear up to sounds around 120 to 150 kHz show high-frequency hearing loss. Hearing loss is highly associated with being stranded on land, though moderate hearing loss seems to be very common amongst belugas (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). All in all, the background noise measured relative to the average noise floor of a beluga habitat can greatly affect the beluga's hearing capabilities. Castellote et al. (2014) suggest that low environmental ambient noise allows for belugas to demonstrate their sensitive hearing thresholds.

Figures 1 (above) & 2 (right): (1) Audiograms of hearing loss amongst 26 belugas of varying ages and different genders. Notice the big differences in audiogram A of belugas with moderate hearing loss to those with normal hearing. (2)

These wild belugas reacted to people singing Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston!

Juno - a captive bred beluga - enjoys a violin performance at the Mystic Aquarium (a safe haven for belugas born in captivity)

Picture Credits and Licenses - Title Image (scaled to fit into column): "Beluga Whale - Shedd Aquarium, Chicago" by Katy Silberger is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0